Margot Noel has a condition called misophonia, which literally means “hatred of sound”. It can be so disturbing that she has to wear headphones or ear plugs to protect herself.

Someone takes a bite out of an apple.

There’s a drawn-out crunch as the teeth break through the tough skin of the fruit.

The noise is unbearable for 28-year-old Margot Noel.

“I have to leave or cover my ears. I just cannot hear it,” she says.

“It puts me in a state of distress, it makes me really anxious. My body feels there’s danger – I need to leave or I need to protect myself.”

Margot has misophonia, which she describes as a brain dysfunction that causes common sounds to produce an intense emotional response – such as anger, panic, fear or distress.

In people with this condition, the part of the brain that joins our senses with our emotions – the anterior insular cortex – is overly active and wired up to other parts of the brain in a different way.

There are many possible trigger sounds, but some of the most common are related to food – crunching, slurping or sipping.

Margot’s trigger sounds include the crunching of crisps, whispering, clicking noises made with pens, keyboard tapping and one of the worst – knuckle cracking.

“My reaction to this one is really physical because it’s one of the worst for me,” she says.

“It makes me jump off my chair and I’ll have to do something to make it stop, which is not the case with all of my other triggers.

“It’s not like a sound you don’t like, it’s much more than that, it’s completely different. It’s something I feel in my stomach, like extreme anxiety. Or suddenly I feel overwhelmed, I can’t think any more, it just takes over everything.

“If someone had a gun and they were pointing it at me, it would feel exactly the same.”

Find out more

- Margot Noel spoke to Outlook on the BBC World Service

- Download the podcast for more extraordinary stories

According to the British Tinnitus Association’s website, trigger sounds tend to be “human-generated noises that are under voluntary control“, such as sniffing.

But if Margot sniffs herself, that’s different.

“I can stop doing it if I want, so it’s not as threatening as someone else doing something that you can’t control and you don’t know how long it’s going to last for,” she says.

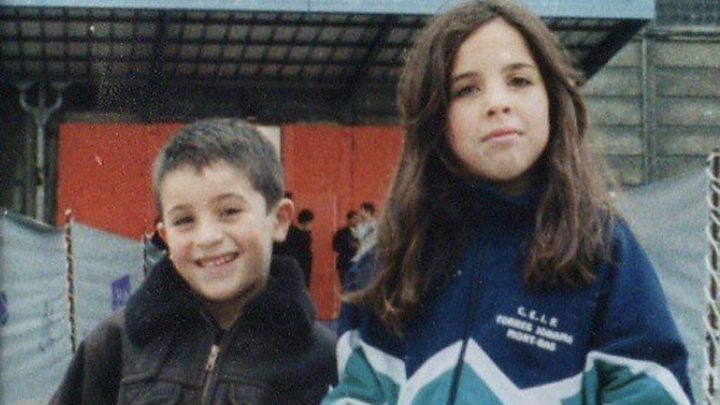

Image copyright

Margot Noel

Margot as a young child

One of her earliest memories is of her brother tormenting her by clicking his tongue.

“I’m about six or seven and it’s a constant fight between us,” she says. “My brother knows that tongue-clicking is a problem for me, I’ve said it a few times, so now he has power over me and he’s two years younger than me. If I annoy him, if I don’t do something he wants, he will just start tongue-clicking.”

Margot’s parents didn’t understand how the noise was affecting her and so would tell Margot to “grow up,” and put up with it.

Now they are older, Margot says her brother is much more understanding, but she is reluctant to complain if he makes a sound that is excruciating to her.

“I was having dinner with my brother yesterday. I gave him a gum after dinner and he was chewing it like a cow, it was horrendous, and I didn’t want to ask him to chew less loudly, because people usually get offended,” she says.

“They feel like it’s an attack or a criticism when it’s not, it’s actually not. I’m the problem, but it’s very difficult to ask people to make less noise because they always end up feeling like they can’t be themselves around you.”

Image copyright

Margot Noel

Although she says she’s had the condition all her life, she didn’t realise it was misophonia until about three years ago.

“It was becoming clearer that I had a problem and I couldn’t find what it was. Sometimes you’re looking for something and you just don’t have the right keywords on Google.

“One day I was really angry and I was crying, because I was watching an amazing play and I was just distracted the whole time by someone breathing like they were going to die, and I went back home, looked again, again, again and then I found it, and from that moment, to be honest, it was really great just understanding.”

Margot also discovered, via Google, that a study into misophonia was being conducted at Newcastle University and emailed the person in charge, Dr Sukhbinder Kumar, to thank him.

He wrote back, and soon invited Margot to take part.

What is misophonia?

Also known as Selective Sound Sensitivity, misophonia is a strong emotional response to the presence or anticipation of a sound. There are three key emotional responses: anger, disgust and anxiety, with anger being the predominant emotion.

These intense emotions are accompanied by high levels of arousal – the fight or flight response. There is a release of adrenaline and a supply of energy to respond to the threat. This is typically experienced as a fast heart beat, rapid shallow breaths, tension, hotness, shakiness, and sweating.

Work environments, such as open plan offices, can be a minefield of triggers. Tensions can develop within intimate relationships and couples can find it difficult to share normal activities together, as someone breathing or eating can become infuriating.

Source: British Tinnitus Association

The trial was terrifying. She had to listen to some of her trigger sounds without reacting to them or even closing her eyes.

“I had wires all over my face, everywhere, and they were studying my reactions to the sounds and I just couldn’t do all of it,” she says.

“It wasn’t that I gave up, because I told them I wanted to do it, but they said I had to stop because I was too distressed and it was confusing the results.

“I think I had to do six modules and I only did two, and after two I was just crying like I’d never cried before.”

Image copyright

Margot Noel

Margot found the trial so distressing because she could not use any of her usual coping mechanisms to escape the trigger sounds. In day-to-day life she wears ear plugs or headphones to block the noises out.

“I cannot live without music,” she says. “My headphones are on my ears all the time, even if there’s no music in them – just ready to rescue me if something happens. Music for me feels very much like a protection.”

Artists such as Moby, David Bowie, Air, Diana Ross, Oasis and Daft Punk have become the soundtrack to her life, she says.

Margot’s anti-misophonia playlist:

- Moby – Inside

- Moby – One of these mornings

- Moby – Another woman

- Air – Talisman

- Air – La femme d’argent

- Air – Le soleil est près de moi

- David Bowie – Ashes To Ashes

- David Bowie – Starman

- David Bowie – Drive-In Saturday

- Tommy Tee – Aerosoul

- Daft Punk – Make Love

- Daft Punk – Emotion

- Aphex Twin – Heliosphan

- Rappin 4 Tay – Playaz Club

- DJ Mehdi – Signatune

Even watching a film can be difficult.

“I hate, for example, the sound of people kissing. That disgusts me, I find it ‘aargh!!'” she says. “One film out of two has people kissing passionately. Some films they don’t make too much sound, but in others they do and I’ll just have to cover my ears and wait for it to be finished.”

When it comes to her own relationships, however, misophonia has not caused any problems so far.

“I try to surround myself with people that are understanding,” she says.

“For me it would be a major downer if I was with a guy and I told him, ‘Can you stop cracking your knuckles?’ and he made fun of me. That would be an absolute no no for me. I’d be like, ‘Well, goodbye.’

“I think if people like you they just try to like all the little things about you, even the ones they don’t really understand. If you really like someone you don’t want them to feel uncomfortable, you want to make them happy.”

Margot is currently seeing someone and has a good social life, but says living with misophonia can be very isolating. She lives on her own, which she says is a “dream,” and works as a freelancer for advertising agencies.

“I’m quite solitary. I write a lot, alone, in my office, like a tortoise,” she says.

Dr Sukhbinder Kumar says there is no scientifically validated method to cure misophonia, but that cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has shown some initial positive results.

It’s also not clear how many people have the condition, he says, though he points out that one study conducted among undergraduates showed that as many as 20% had significant misophonia symptoms.

Margot often doesn’t tell people about her own symptoms as she finds they are not always sympathetic – and sometimes even think it’s something she has invented.

“I just try to deal with it on my own without asking people to change their behaviour,” says Margot.

She hopes the study she took part in will eventually lead to new treatments. But also looks forward to a day when more people know that the condition exists.

“If I could just ask someone next to me in the theatre, ‘I’m sorry, can you just try to not do that noise, I have misophonia,’ and they would be like, ‘Oh I’m really sorry,’… That is what I’m hoping for more than a treatment – just being able to have that discussion with someone without them making me feel like I’m a freak.”

Listen to Margot Noel speaking to Outlook on the BBC World Service

Join the conversation – find us on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and Twitter.